Journey from Silkworm to Saree

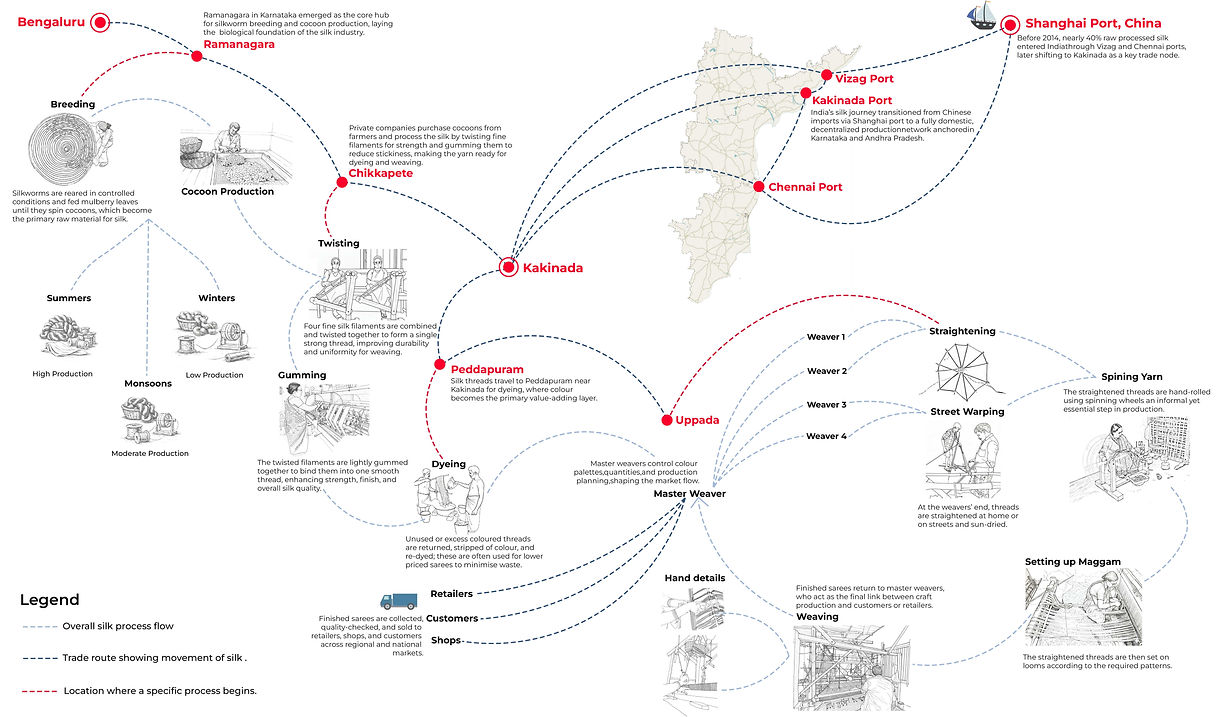

The silk saree follows a long and layered journey. Before the Make in India movement in 2014, nearly 40% of silk was imported from China through Shanghai Port to Vizag and Chennai. Before 2003, silk moved directly from breeders to master weavers, making the Vizag–Kakinada route convenient. With the entry of private companies, silk processing shifted to Bengaluru, and Chennai became the main import port.

After 2014, silk sourcing became fully domestic, with Ramanagara, Karnataka, emerging as the key centre for silkworm breeding and cocoon production. The silk is then sent to Chickpet, Bengaluru for twisting and gumming to strengthen the filaments.

Dyeing takes place in Peddapuram, Kakinada district, based on colour choices from Uppada’s master weavers. The dyed silk is sent to Uppada, where threads are distributed to weavers, straightened at home or on the streets, and wound into rolls. The maggam is set up in 3 to 7 days, and weaving a Jamdani saree takes about 20 to 25 days. The finished sarees are returned to master weavers for sale to shops, retailers, and direct customers.

Transformation of Weaving Economy

To understand the transformation of houses, the drawing traces the shifting economy embedded within domestic space.

Weavers are paid daily wages of approximately ₹800 – ₹1,000, while production takes place almost entirely within the home. As a result, domestic space functions not only as shelter but also as a productive economic unit, constantly negotiating labour, income, and spatial use.

As the silk economy fluctuated due to changing demand, rising costs, and generational shifts, houses were compelled to adapt. Periods of economic stability led to extensions and workspace expansion, while declining returns resulted in rooms being repurposed, rented, or gradually withdrawn from weaving activities.

Typological Shift

The settlement reveals a gradual typological transformation shaped by livelihood and mobility. What began as uniform single-storey units expanded horizontally during periods of intensified labour and production. As families sought greater separation between domestic life and work, ground plus one structures emerged, while mixed-use buildings developed when weaving declined or ceased.

Over time, the housing typology moved beyond purely residential use to become hybrid, layered, and temporal. It reflects the long-term effects of environmental displacement, economic fluctuations, and shifting social aspirations. Not all families continued weaving. Education, migration, institutional employment, and religious networks opened alternative pathways, particularly for younger generations.

These occupational transitions directly reshaped domestic space. Rooms once occupied by looms were converted into classrooms, storage areas, or rental units, while upper floors replaced ground-level workspaces. Gradually, productive and domestic zones became spatially separated. The house thus emerges as a material record of adaptation, aspiration, and exit, rather than continuity alone.