Topographic Playfield

- Kewal Mehta

- Aug 8, 2025

- 2 min read

Landscape Design

Studio Co-ordinator: Ravindra Punde

Kewal Mehta

In cities like Mumbai, public open spaces often become contested, shaped by walls, rules, and exclusions. Parks get gated. Maidans turn into single-purpose fields. What disappears is the idea of the “commons” , a shared space that belongs to everyone. The design exploration grew from a desire to reclaim that idea through landscape, by reimagining how landform itself can make public space more open, inclusive, and democratic.

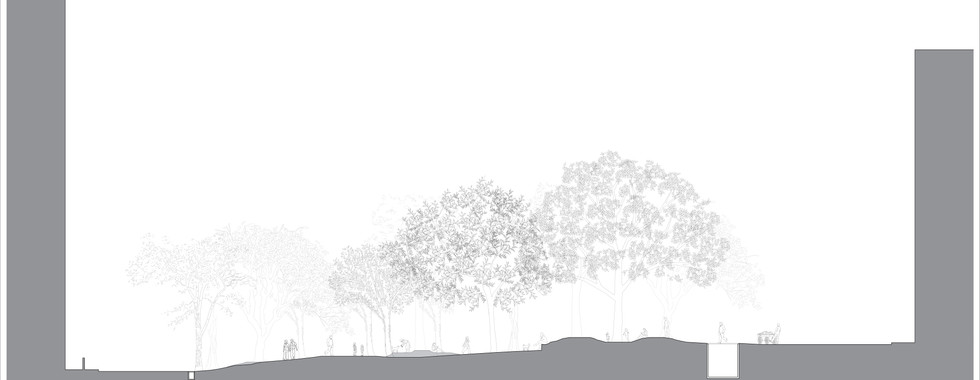

The site, a maidan within a dense residential neighborhood, was once a flat, neutral ground. While open, it lacked comfort, shade, and sensory richness. The question was simple: how can the ground itself invite participation? Instead of adding layers of built form or rigid programs, the design began with the topography with mounds.

Mounds became the tool for shaping openness. By gently lifting and folding the earth, new forms of experience emerged places to sit, climb, view, rest, or gather. The landscape became fluid, no longer prescribing where to play, where to walk, or where to pause. Unlike flat, programmed grounds that dictate use, these undulating surfaces encourage self-determination. A mound might be a hill to a child, a seat to an elder, or a quiet refuge to someone seeking solitude. The topography itself becomes democratic free of hierarchy, open to interpretation.

Planting further reinforces this inclusivity. Trees were not placed merely for ornament, but for the experiences they create shade, fragrance, and memory. Large-canopy species provide rest and refuge, while flowering trees mark the passing of seasons through scent and colour. Together they form microclimates of care shaded walking loops, cool sitting areas, and vibrant edges that draw people in. Through this approach, planting becomes a participatory act, a living medium that invites people to connect through touch, smell, and movement. Ecology and experience merge to create an environment that feels both intimate and shared.

Democracy in landscape design is not just about removing fences, it's about opening possibilities. In a mound-based landscape, there are no fixed zones or rigid programs. The same mound can host morning yoga, afternoon games, or evening conversations. The space evolves with its users, adapting to the multiple rhythms of urban life. This fluidity transforms users into co-creators. The park is not a spectacle to look at but a framework for interaction, a place where life unfolds organically and collectively.

The beauty of such landscapes lies not in manicured precision but in empathy in how they allow for rest, play, and connection without exclusion. The mounds, slopes, and textures offer comfort and invitation, transforming a once-flat ground into a living commons. At a time when urban open spaces are increasingly commercialized or privatized, this approach offers an alternative vision, one where design becomes a tool for inclusion, not control. By reshaping the ground itself, we reclaim the idea of public space as a shared right, not a managed privilege.

In the end, the question that drives this exploration is simple yet powerful: What if every park was designed not just for people to use, but for them to belong to?

Comments