Computational Logics

- Upanshu Sakhala

- Aug 30, 2025

- 4 min read

Waiting Spaces

Studio Co-ordinator: Dushyant Asher, Tushar Rajkumar, Manasvi Patil, Anuj Daga

Upanshu Sakhala

The computational design module in my first year of architecture college was honestly one of the most fascinating experiences till now, because it was also our first proper design studio in college. Introduced in the 3rd semester, the module came immediately after the one that included our Ahmedabad study tour, where we were first exposed to the idea of “Type” and began to understand what typology means in relation to architecture. This sequencing made the transition into computational design feel grounded, as we were already thinking about how architecture responds to history, context, and recurring spatial patterns.

The module felt like an entry point into how architects actually think, not just how they draw or make pretty forms. Through it, design stopped feeling like guesswork and instead became a process built on logic and observation. The faculty made us realize that every line, every space, and every volume needs a reason, and that this reason can come from history, typology, site conditions, or user behavior. We were introduced to the concept of computational logic and encouraged to approach design methodically, with a clear intent guiding every decision. This was done through a series of lectures that included detailed explanations and a wide range of examples, helping us understand how systems, rules, and logic can shape architectural outcomes.

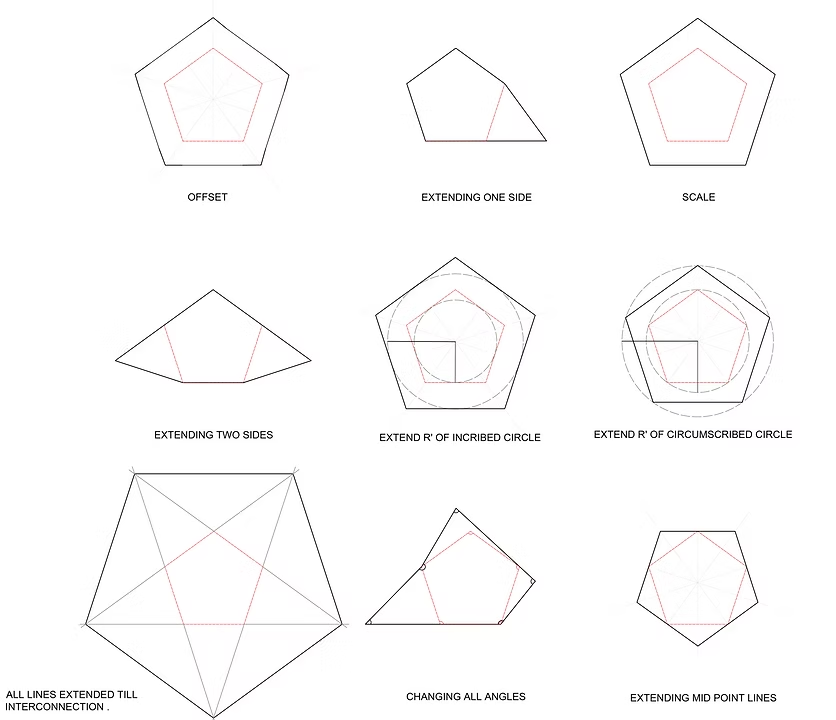

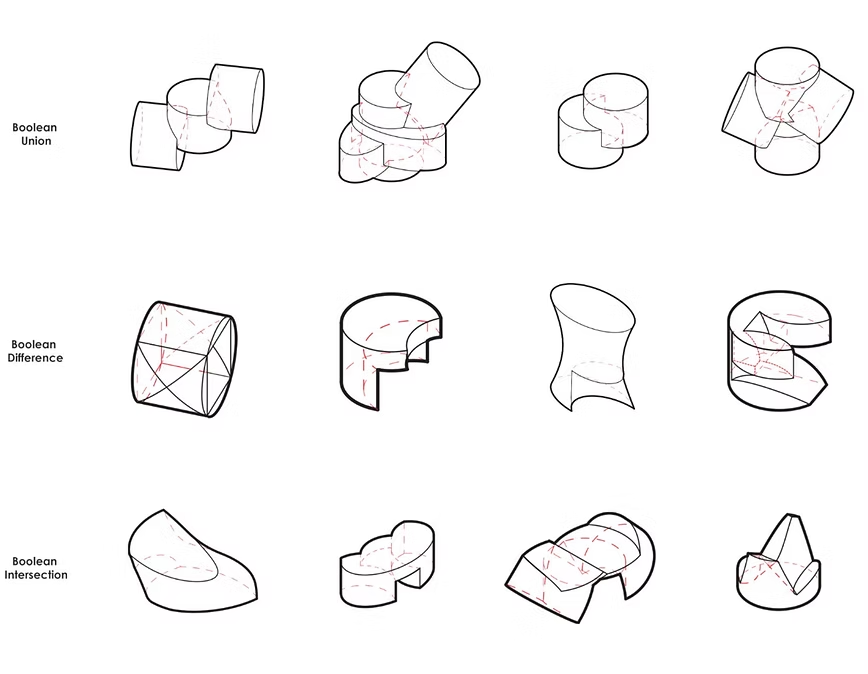

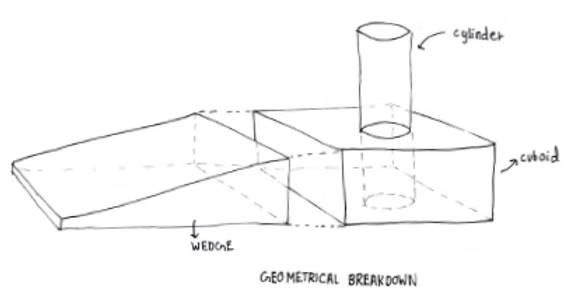

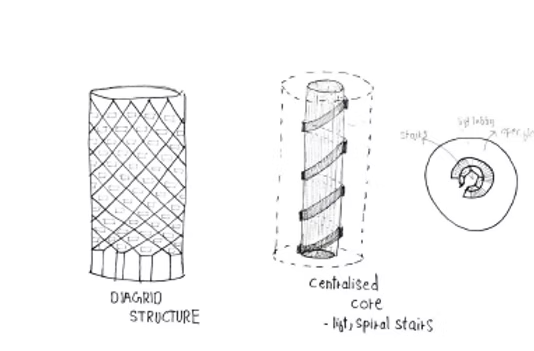

Learning how to apply Logics to generate forms using basic shapes

One of the key ideas introduced during the module was typology and its relationship to history and context. Studying typology helped me understand that spaces evolve over time based on culture, technology, and user needs, and that as designers, we are not working in isolation but are always responding to something that already exists. This way of thinking provided a background layer for design, allowing me to move away from starting with a blank page and instead begin with an understanding of how similar spaces have been organized in the past and how they function today.

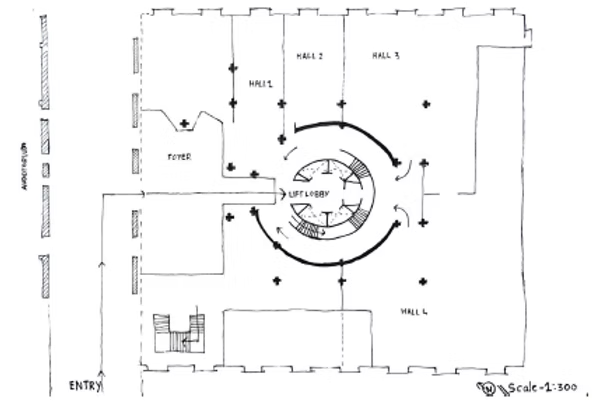

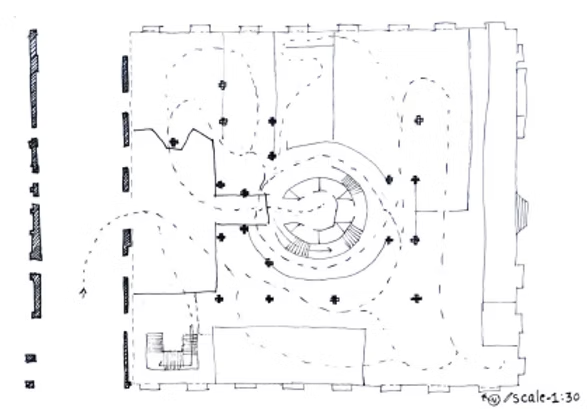

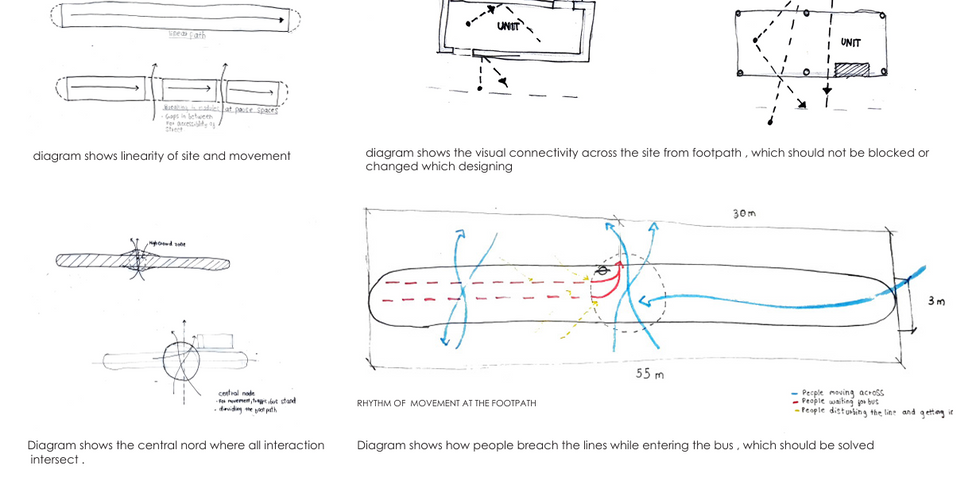

Diagramming became another very important part of the module, and it completely changed the way I look at architectural drawings. Earlier, I thought diagrams were simply quick sketches with arrows, but here they were treated as serious design tools. We learnt that diagramming is a way of breaking down a complex reality into simpler layers such as movement, noise, light, activities, pause points, and edges. Instead of jumping directly into plans and sections, we first translated our site observations into diagrams, which helped reveal hidden relationships and patterns. These diagrams then became the base from which our design decisions grew, ensuring that the final form remained connected to actual site conditions.

Learning Diagramming and Type through case studies - Nehru History Centre

For the main studio exercise, the class was divided into four groups, with each group assigned a different site. The sites included Mandapeshwar Caves, the Borivali East railway station exit, the entrance of Sanjay Gandhi National Park, and the Gorai jetty point. Each group visited their respective site to analyze the site conditions and observe the features and characteristics that stood out most strongly. My group was given the road outside Borivali East railway station, which is a highly active and chaotic urban space marked by pedestrians, vehicles, vendors, and constant waiting.

After documenting the site through sketches, photographs, plans, sections, and written notes, we began working individually on our designs. The process started with creating observation diagrams based on the site, which were then used to develop the design in response to the given brief. The brief required us to design a waiting space for 15–20 people, along with one or two additional programs integrated into the waiting area. My own focus was on the movement of people, and by mapping their flows and pauses, I was able to gradually shape the space, deciding where it should open up, where people could sit, and how circulation could remain unobstructed.

Alongside this, the most exciting part of the module for me was getting a first taste of what computing and computational design mean in architecture. It was not only about using software, but about learning to think in terms of rules, systems, and parameters. We were introduced to ideas such as generative form finding, where certain conditions are set and forms are allowed to emerge, and analytical form finding, where performance and data are studied to refine the form. This approach made geometry feel more alive, something that could be generated, tested, and transformed logically rather than drawn once and kept fixed. Throughout the process, logic development remained in the background, constantly pushing us to justify why a form bends, opens, tilts, or compresses.

The entire design evolved through physical models and sheet work, with each iteration refining the form further. Eventually, this process led to digital drawings and rendered views, which felt like a natural conclusion to a long journey rather than just a final presentation.

Overall, the computational design module established a structured approach to architectural thinking, grounded in typology, site observation, and logical systems. By integrating diagramming and computational reasoning into the design process, the studio reframed form-making as an outcome of analysis, intent, and iterative exploration rather than intuition alone.

Comments